Border trade is a boon for Thai SMEs, but they should not be complacent

Thailand’s total exports have fallen for two straight years, but the outlook for trade with the four countries on the nation’s borders is bright. Demand for Thai products from buyers in Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar in particular has been rising fast, in tandem with their booming economies. International investors are clambering to set up operations within these countries in order to tap the local markets, but Thai companies have a next-door neighbor advantage. Thai products are already well known in these countries and considered high in quality. This is driving border trade in general and allows Thai small and medium-size enterprises (SMEs) to grow their sales abroad without ever leaving Thailand. But Thai SMEs should not be complacent. Consumer trends are changing fast in these countries, and domestic competition is heating up. EIC recommends SMEs to enter these nascent markets directly and target consumers carefully. Customers there, most of them young, do not yet have strong brand preferences. Gaining product recognition and brand loyalty now will give Thai businesses a strategic advantage over future competitors.

Author: Veerawan Chayanon

|

Highlight Thailand’s total exports have fallen for two straight years, but the outlook for trade with the four countries on the nation’s borders is bright. Demand for Thai products from buyers in Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar in particular has been rising fast, in tandem with their booming economies. International investors are clambering to set up operations within these countries in order to tap the local markets, but Thai companies have a next-door neighbor advantage. Thai products are already well known in these countries and considered high in quality. This is driving border trade in general and allows Thai small and medium-size enterprises (SMEs) to grow their sales abroad without ever leaving Thailand. But Thai SMEs should not be complacent. Consumer trends are changing fast in these countries, and domestic competition is heating up. EIC recommends SMEs to enter these nascent markets directly and target consumers carefully. Customers there, most of them young, do not yet have strong brand preferences. Gaining product recognition and brand loyalty now will give Thai businesses a strategic advantage over future competitors

|

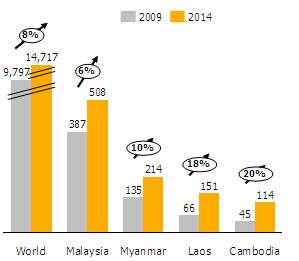

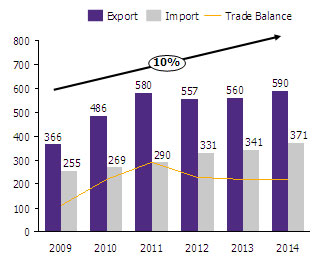

Border trade is the dominant channel for Thailand’s imports and exports with neighbors. Transactions near shared borders accounted for 70% of Thailand’s total trade with Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar and Malaysia (CLMM) in 2014. Malaysia is Thailand’s top border trade partner among CLMM, accounting for 50% of all border trade (Figure 1). Nevertheless, Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar (CLM) are promising new markets, reflected in double-digit percentage growth in their border trade last year, and 20% in the case of Cambodia, far above the 8% YOY growth in their global trade (Figure 2). Although Thailand’s trade account has been in deficit since 2011, the nation’s border trade has been in surplus (Figure 3).

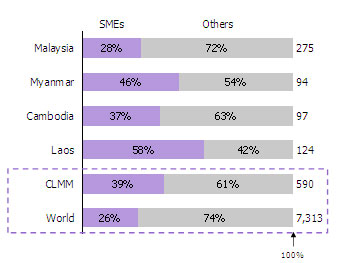

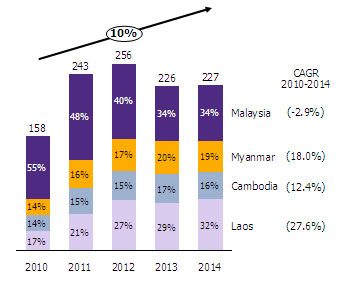

The growth of Thai SME earnings from border exports was five times that of global exports, proving that golden international opportunities are close at hand. Border trade allows faster delivery and lower transport cost compared to more far-flung types of trade. And nearby countries are often more familiar and accessible to Thai SMEs than other international markets. EIC notes that SMEs account for 40% of Thailand’s total border exports by value (Figure 4), whereas SME exports claim just 25% of Thailand total exports to all international markets. Moreover, growth in border exports by SMEs, at 10% in 2014 YOY, was five times the 2% growth in SME exports to the overall global market (Figure 5). Proximity and growth both position border trade as a good starting point for business owners looking to develop their exports.

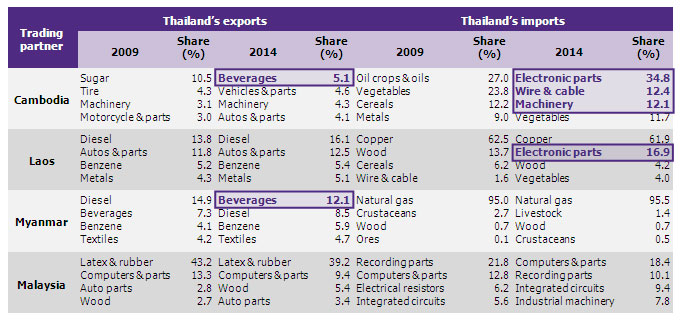

Even though demand for consumer goods in border markets remains strong, businesses should adapt to the fast-evolving needs of consumers. The CLM countries collectively achieved GDP growth of 7% YOY in 2014. The rise in income raises purchasing power and creates demand for a wider range of consumer products. Consumption is shifting from basic goods like farm products toward more sophisticated goods that better suit urban living. Cambodia shows this demand transition. In 2009, its top import from Thailand was sugar products. In 2014, it was soft drinks, beer and beverages. Similarly, Myanmar’s top imports from Thailand are now beverages, displacing diesel fuel (Figure 6). Thailand’s border trade has likewise been changing on the import side. In the past, Thailand used to import mostly primary products such as vegetables, metal and wood from Laos and Cambodia. Today, Thailand buys mostly intermediate products for use in producing finished goods like televisions and cars. This change has partly resulted from relocation of factories making electronic parts. Thus not only consumer trends but also the evolution of supply chains opens up new opportunities for Thai businesses that adapt.

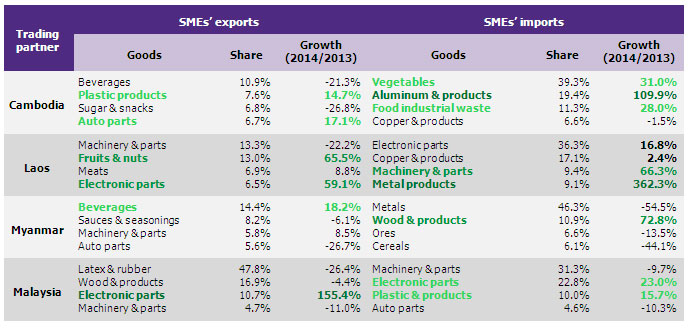

The big growth in SME exports of modern consumer products reflects increasingly diverse demand, creating both opportunities and challenges for businesses. Although border-trade demand for SME products resembles the overall trend, growth in exports of consumer products like beverages, snacks and plastic goods is particularly notable (Figure 7). This is because these markets, especially CLM, are short on production capacity to meet the rising domestic demand for modern, western-style products. Moreover, consumers there are now willing to spend more on comfort. Thai companies benefit from having strong domestic standards for quality, especially among the leading brands. Nevertheless, the majority of consumers in CLM still have limited purchasing power and thus focus mostly on necessities – for example, processed foods or energy drinks. Yet there are a few consumers who earn enough to be willing to pay for luxury clothing and premium electronics. SMEs therefore need to understand the specific trends among different segments in these flourishing markets in order to provide the right products.

E-commerce is another promising channel to benefit from border markets because it allows SMEs to act as intermediaries between suppliers in border marketplaces and Thai consumers. Many Thai SMEs have been using e-commerce as a new platform to support their border-trade activities. Via websites and social media, they post ads for products from the border marketplaces. Products are then sent by mail. For example, in the first half of 2015, the volume of postal deliveries from Rong Kluea, a marketplace in Sa Kaeo Province near the border with Cambodia, rose by 35% YOY. The majority of the products shipped were clothing, shoes and appliances imported from Cambodia. Trade opportunities are therefore no longer limited to companies physically located at the border. SMEs do not need to import products by themselves, but instead can intermediate trade flows between the border marketplaces and customers all over Thailand. As e-commerce becomes popular in Thailand’s neighboring countries and delivery services broaden their geographic coverage, Thai SMEs may also expand their offerings into these countries in the future.

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 1: Thailand’s border trade in 2014: by partner and share of total trade

Unit: %, Billion THB

*Other trade is shipments by air or sea or from free-trade zone.

**Border trade is imports and exports that travel by hand, car,

truck or rail and pass through customs at the nation’s four borders.

Source: EIC analysis based on data from Department of Foreign Trade

|

Figure 2: Thailand’s border trade in 2009 vs. 2014, by partner |

Figure 3: Thailand’s border trade flows by year, 2009-2014 |

|

| Unit: Billion THB |

Unit: Billion THB, % CAGR of export value |

|

|

|

|

| Source: EIC analysis based on data from Department of Foreign Trade | Source: EIC analysis based on data from Department of Foreign Trade |

| Figure 4: CLMM SMEs’ share of border exports in 2014 |

Figure 5: CLMM SMEs’ border exports by year, 2010-2014 |

|

| Unit: %, Billion THB |

Unit: %, Billion THB |

|

|

|

|

|

Source: EIC analysis using data from Department of Foreign Trade and Office of Small and Medium Enterprise Promotion, Ministry of Commerce |

||

Figure 6: Leading goods traded across Thailand’s four borders in 2009 and 2014

Source: EIC analysis based on data from Department of Foreign Trade

Figure 7: Leading goods traded by Thailand’s SMEs across borders in 2014

Source: EIC analysis based on data from Office of SME Promotion